I intended to become a writer upon entering the service. It was even part of my motivation to enlist. So, when I came across interesting people and conversations, I wrote them down. This memoir is about my earliest days in the Navy squadron that was my first assignment, and the changes I went through after meeting my militant roommate. The only fictionalized name is Janaszek because I didn’t remember it at the time.

What you see here is a bit of a rewrite. The original was published in the 2018 edition of Ageless Authors Anthology.

The photo of me was taken near my barracks at NAS Atsugi in the Fall of 1969 using my camera. I don’t remember which one of my new friends snapped the picture.

The room across the hall from the master-at-arms’ office exploded into what was clearly a fistfight. Just as suddenly, silence, except for some guttural cursing. A petty officer second class walked out, brushing himself off. He was a tall, meaty man with a lustrous black mustache and “Martinez” stenciled over his denim work shirt pocket. He saw me, and a smile lit up his face. “You must be the new guy, Smith.”

I nodded. It was a late September dawn in Japan, 1969, and I had just stepped off the bus from Yakota Air Base to report to my first assignment. After fifty-plus hours with little sleep while in transit from San Diego, I felt beat ragged. Following him into his office, I tilted my head towards the recent melee and raised my eyebrows.

“Oh, that,” Martinez said. ”Just waking up that asshole Janaszek, who can’t seem to hear an alarm. He comes up swinging at the poor slob on duty who has to rouse him for his flight back to Cubi.”

He noticed my confusion. “To our detachment in Cubi Point, Philippines. Where he’s stationed.”

Martinez said the first time he woke Janaszek up, he got hit without warning and automatically hit him back. He thought he’d get court-martialed, but nothing happened. Now he likes to wake him up because he gets to punch a jerk who outranks him with no repercussions. He said it was possible that Janaszek just doesn’t remember anything before coffee.

“And anyway, everyone knows he’s a son-of-a-bitch.”

Martinez sat down as I sagged under the weight of my sea bag. Sitting open on his desk was a thick book with dozens of torn paper bookmarks propped up on a copy of Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy.

“Hefty tomes,” I said.

“So close to getting my bachelor’s degree,” Martinez replied. “College man?”

“A year at North Texas State,” I replied. “Planning to finish on GI Bill.”

“All right! We’ll talk. Let’s get you a place to stay, Smitty. Then, you can check in with Personnel.”

“Any chance of getting some sleep?” I asked.

“Tonight. You might as well adjust to time on the other side of the world,” Martinez said while looking at a chart on the wall. “Here it is. You’re bunking with Ray Hill.”

He rose and motioned for me to follow. We walked down the main hall between cubicles with dark drapes for doors. With a flourish, he opened a curtain. “Hill. Here’s Smith, your new roomie. You good with that?”

An unembodied voice replied, “It’s cool.”

Martinez turned back to me. “We hope you enjoy your stay.”

“Thanks, Martinez.”

“Call me Marty,” he said, strolling away.

I stepped into the cubicle and, with a sigh of relief, let my burden drop.

My roommate was standing in front of a hefty green Naugahyde chair holding an open paperback in his left hand. He continued to read, not looking up to see who his new roomie was.

A nicely-shaped white hat perched atop what passed in the Navy for an afro. His starched and pressed dungaree work shirt sported his rank and rate on its left sleeve: petty officer third class, aviation structural mechanic. Despite the general gloom of the barracks, he wore heavily tinted glasses with thick black frames.

He also had on black, Navy issue socks, but no pants.

I introduced myself: “Hi. Smith. New guy. Uh, nice legs.”

Hill said nothing.

“New guy?” I continued.” This rack OK?” I pointed at a bare lower bunk.

Hill spoke: “Smitty, come the revolution, you’re gonna have to go up against the wall.”

I looked at him askance before inspecting an empty locker. “Well, you wake up cheery,” I said.

Hill continued: “You should be aware that because of Vietnam, America is training thousands of black men in all aspects of war. We are learning to speak the white devil’s language of violence.”

“Everything is hopelessly wrinkled,” I said after dumping the contents of my seabag onto my new bed.

Hill sat down, held up the paperback, and began reading:

“The existence of violence is at the very heart of a racist system. The Afro-American militant is a ‘militant’ because he defends himself, his family, his home, and his dignity. He does not introduce violence into a racist social system—the violence is already there and has always been there. It is precisely the unchallenged violence that allows a racist social system to perpetuate itself. When people say they are opposed to Negroes “resorting to violence” what they really mean is that they are opposed to Negroes defending themselves and challenging the exclusive monopoly of violence practiced by white racists.”

Hill’s voice had gotten louder, and his hands shook slightly toward the end.

“That sounds about right,” I said. “So, where you from?”

Ray glared at me, then softened, shaking his head. “Houston. You?”

“Dallas,” I replied.

“Texas, too? Where’s your redneck accent?” Hill asked. He picked up a pair of dungarees that lay folded on his bed.

“No idea, but I can put it on when I have to deal with bubbas.”

“Don’t we all,” said Hill with a snort. He stood and pulled on his pants.

Meanwhile, I shifted my possessions from the bed to the locker. “Is there a laundry?” I asked.

“Across the street and down a bit,” Hill said, waving his hand in the general direction. He sat back down.

Hill laced up his flight boots as I arranged my stuff.

“I’d like to think things are changing,” I said.

Hill jumped to his feet. “Martin’s down, Malcolm’s down! J.F.K. and Bobby are down! Angela and Eldridge are on the run! Even the damn writer of this book is on the run! You think things are changing, Smitty? I’ll tell you what’s changing: Black America has finally realized that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun!”

“Wow, Mao,” I said.

“I’m trying to be serious here,” Hill said.

“Sorry.”

Scowling, Hill said: “That’s just disrespect, man. Making a joke out of this is just another example of whitey blowing off the black man’s concerns, ’cause you so important and we don’t matter!”

His right hand clenched into a fist.

He said I was waltzing in here acting like I owned him, just like my great-great-granddaddy owned his ancestors. Then he made a few disjointed comments about whites murdering and terrorizing his people before he stopped talking and sighed in exasperation.

His fist relaxed and fell to his side.

I held out my hands. “I’m sorry, Ray. Sorry. Been awake for a couple of days.”

Hill collapsed into the chair.

“Look, smart-ass remarks are just me. And, I didn’t come in here because I think I own you, it’s Marty’s fault. He assigned me here.”

I grinned, but Hill merely stood up, and without looking at me, reached into his locker and pulled out a gym bag.

“I’m just saying that there’s a lot of noise about civil rights,” he said softly, “but it ain’t manifesting on the street.”

He moved his shaving kit and changes of clothes into the bag. I sat at the steel writing desk and turned the chair to face Hill. “What’s this book you’re reading?”

He smirked. “Know many black authors, Smitty?”

“Uh, I have a copy of Ellison’s The Invisible Man, but I’ve only skimmed it. But I have read the ‘Ballots or Bullets’ speech by the X guy and Reverend King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech.”

Hill gasped. “You, a southern white boy, read a speech by Malcolm X?”

I shrugged. “I read a lot.”

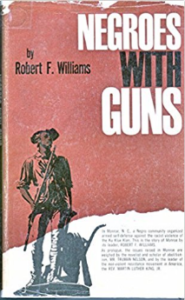

Hill zipped up the duffel and sat it on the bed. “It’s Robert F. Williams’ book, Negros with Guns.”

Hill zipped up the duffel and sat it on the bed. “It’s Robert F. Williams’ book, Negros with Guns.”

“Yikes,” I said.

“Yeah. The white reaction. Williams talks about that in the book. But all he’s saying is that it’s the right of all Americans, when the police won’t, to act in self-defense against lawless violence.”

I nodded. “It is our right, but Reverend King had some things to say about that.”

“King is dead,” Hill interjected.

“Maybe he died to save our souls.”

“Maybe he just got gunned down by a dumb-ass cracker!”

“Maybe both?” I suggested.

Hill paced the cubicle. “Yeah, yeah,” he muttered.

“Oh, and I read Eldridge Cleaver’s book, Soul On Ice.” I made a “so-so” gesture with my right hand.

Hill stopped pacing. “What?”

The doors at the end of the hall banged as they opened and closed. Footsteps echoed. “Hill!” someone called. “Truck’s out front. Let’s move!”

Ray filled me in as he slipped on his flight jacket: “Doing ops out of Cubi Point. Be back in a few weeks.”

I nodded. ”I’ll keep a watch over the place.”

“Here,” Hill said as he handed Negros with Guns to me. “Read it. Tell me what you think.”

“Gee. Thanks.”

A smile broke across Hill’s face. “You know, I like you, Smitty. But come the revolution, you’ll still have to go up against the wall.”

He turned and walked through the curtain.

With a chuckle, I called out to him: “Nice to meet you, too!”

Hill’s short laugh merged into the sharp sound of footsteps on waxed and polished asphalt tile. Heavy steel doors banged open and shut.

Two days later, I wandered into the master-at-arms’ office to chat before heading to the hangar. Martinez was slumped in his chair, staring at nothing.

“Marty? You OK?”

He appeared much older as he looked up.

“I just heard.” He paused. “Just heard. Our flight went down. South China Sea. Approaching the Constellation.”

“I just heard.” He paused. “Just heard. Our flight went down. South China Sea. Approaching the Constellation.”

He paused again. Then, almost inaudible, “No survivors.”

“Hill?” I asked.

Martinez nodded. I felt a cavernous ache inside.

He continued: “Dilger, Livingston, Tye.” There was a catch in his voice. “And Moser!” A deep sigh rumbled from his chest.

Stunned, I sat down and quietly mourned with him.

For the next few days, grief-saturated silence filled the squadron’s hangars. During that time, I lived with a phantom roommate. Despite his lack of corporeality, I greeted and said goodbye to Ray as I came and went.

More than that, I read his book.

Late in the summer of 1962, I was barely 12 when my dad’s service station employee dropped off his child so my parents could watch over him. A medical emergency, I think. He was about my age. He was black.

My folks tried to raise me right; to see people for who they were in God’s eyes and never use the n-word. So, I thought nothing of it.

The first thing I did was take him to the chinaberry trees I liked to climb in the corner of our yard. Then I showed him my favorite place: the wet weather creek behind our house. We explored, got muddy, and did general boy stuff.

Later that afternoon, when we climbed back over the fence into our yard, my mom and dad stood on the patio. They were smiling in a way that I didn’t understand.

Then life went on. For the next seven years, wrapped up in my primarily white teenage world, I didn’t take time to truly comprehend the racial reality of America beyond the platitudes heard in church and school.

But after reading Negroes with Guns, I finally grasped the daily stresses, indignities, fears, and realized horrors that were part and parcel of black life. And, I got how asking people systematically abused by the commercial and legal establishment to be patient further institutionalized that abuse.

Influenced by the ideals of the peace movement, I felt a sense of hopelessness when Williams repeatedly demonstrated that the threat of retaliatory violence was all too often necessary to prevent violence against peaceful citizens exercising their First Amendment rights.

Most crushing was finally absorbing the story behind the stories of Martin Luther King, Dick Gregory, and the Black Panthers, realizing how the nation of my birth failed its promise in the century since emancipation.

Now, I understood my parent’s odd smiles. These people—who had learned as children what it was like to be poor and cast adrift in life, and who I heard in 1960s Texas laugh openly at the idea of racial purity—saw hope for the future in those two happy, muddy boys climbing over their back fence.

Four days after receiving the news about our missing plane, the Officer of the Day came to my cubicle with bolt cutters. Martinez followed, carrying strapping tape and a couple of corrugated boxes. His eyes drooped like his mustache. A big man with big emotions, he could not hide his grief.

The O.D. cut Ray’s lock, causing Marty to flinch. I did, too.

The officer then carefully removed Ray’s personal effects from his locker, announcing aloud what each was. Marty repeated what he said and recorded the data on a form attached to a clipboard. They filled up one box and began filling another.

I sat at the far end of the cubicle and watched my ghost get exorcised.

After the O.D. passed the last item to Martinez, I stood and handed him Negros With Guns. The officer, young and white, looked at the title and grimaced.

“This is his,” I said. “His family needs to have it.” I choked a little. “They need to know that, come the revolution, their son was ready to fight for their rights.”

With a pause and a slight affirmative nod, the officer passed it to Martinez.

Marty looked at me and attempted a smile. Turning back to his form, he noted the book’s title and placed it into the box.

As he yanked the tape from its dispenser, it emitted a mournful shriek.

2 thoughts on “Come The Revolution”

Comments are closed.