This memoir is about my attempts at political activism while in the service.

The drawing is my version of the G.I.’s Against Fascism logo.

A lot of history went down between the day I enlisted in the Navy Air Reserve in March of 1968 and when I arrived in San Diego in September of 1969 to find out where on Earth I would be stationed for active duty: personally, the worldview gained from finishing high school and spending a year in college; globally, an urgent need to resist retrogressive elements in society arose among young adults.

In the Navy and Marine Corps, that collective urge coalesced as G.I.’s Against Fascism just a month before I checked in. It came to my attention when I found a copy of their underground newsletter, Duck Power, in the transit barracks.

Its logo was a crude cartoon of a duck in a sailor’s white hat raising a clenched fist.

Some of their positions were more radical than mine, but the substance of their argument fit my developing political awareness.

Inspired, I drew an interpretation of their logo with a Marks-A-Lot on a large piece of paper. I taped it to the front of my locker door with casual defiance.

Other budding dissidents saw it and wanted a version for themselves. I reproduced my illustration on paper, t-shirts, hats, notebook covers, luggage, and a guitar case.

I drew it on my new black leather gear bag using a white laundry marker.

A week later, orders came down from on high outlawing the group, their newsletter, and the Duck Power image. The symbol’s brief time on the barricades was over. I could no longer carry the gear bag and couldn’t afford to buy another.

Obediently, I removed the drawing from my locker. Promptly, but not nearly as obedient, I drew Duck Power Donald on its inside back wall with the indelible marker.

The next week I received orders to VRC-50, a squadron based at Atsugi Naval Air Station in Japan.

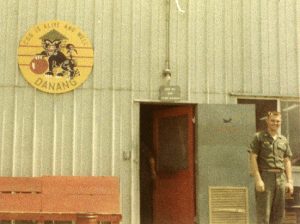

Following an intense three-month hands-on education in how aviation maintenance administration—the maintenance desk, logs and records, and analysis—worked in this squadron, I was assigned to its detachment at Da Nang Airbase.

By the time I landed in South Vietnam, the ambitious plans of all sides in Southeast Asia were FUBAR. The Vietnamese people, North and South, military and civilian, were suffering ghastly losses. Conflicting propaganda filled newspaper columns and airwaves, accurately reflecting the chaotic decision-making by one administration after another. To all appearances, the military’s top brass attempted to fill the leadership gap with tactical thinking unburdened by on-the-ground reality.

American service members began to realize their reward for courage and loyalty would be needless suffering for the sins of a cursed foreign policy. Increasingly, no one wanted to be the last to die for a lost cause.

Seeing this up close shattered my belief that the contemporary role of the U.S. military was equivalent to that of my fascist-fighting father in World War II.

To this day, I grieve. We failed the majority of South Vietnamese, who feared the communists as much as they hated their corrupt homegrown regime and the clumsy sway of American influence.

Despite such misgivings, my comrades-in-arms and I did our jobs very well. I was proud of that but felt the need to alleviate some of the hardship on the locals.

Every payday, I sought donations from members of my squadron and those in VQ-1, an intelligence-gathering squadron that shared a defensible area on the western edge of the airstrip. Airman Phillips, an avionics technician from that unit, and I used those funds to buy soap, toothpaste, toothbrushes, towels, detergent, first aid supplies, etc.

Then I bummed my squadron’s pickup truck and we delivered the goods to an orphanage in Hoi An, an hour south of the airbase—if there were no disturbances.

Whenever I borrowed the truck, my tall, blond, crew-cut Maintenance Chief would hand me a .38 caliber revolver and a box of bullets.

“Don’t get killed,” was his sole piece of advice.

Phillips also organized a small group from both of our squadrons in a campaign to write a letter to every member of Congress to convince them that American strategy in Southeast Asia had gone off the rails. He persuaded us that a Vietnam postmark would mean something in Washington.

The letters we wrote were respectful, attempting to sincerely convey what we saw personally and what we learned from the Marines in the field.

Senator J. William Fulbright and only Senator J. William Fulbright replied. He thanked us for our perspective.

Then the Kent State shootings shocked America. The killing of unarmed protesters didn’t go down well with most young members of the armed services. We’d been led to believe we were risking our lives to continue American constitutional freedoms. The incident was just one more way many of us felt betrayed.

While we were still processing this travesty, a loudmouth hailing from Anchorage joined our detachment.

This new airman was full of macho bluster. Among other boasts, he claimed his father was a sheriff who, unprovoked, shot a hippie in the stomach. As a warning, he said, to let them know they weren’t welcome in his town.

His story was probably bullshit, a usually accepted, even exalted, form of communication in the Navy. Not so in this case; he just made himself odious right off the bat.

Thrilled to be in Vietnam, yet having enlisted in the relatively laid-back Navy, the talky tenderfoot was not close enough to the glories of war roiling his imagination. His second day on base, he asked when he would be assigned to stand guard duty.

One of his fellow structural mechanics pointed out to him that we felt safer relying on Marines—real warriors—to meet that need.

The new guy was appalled but not deterred. To our surprise, the Marines humored him. That evening, he was strutting around the barracks with a .38 caliber revolver strapped to his hip and toting a sawed-off shotgun.

The next morning, a Marine corporal who could not wipe the grin off his face approached the squadron office. He told us that this ersatz gun-slinger decided to practice his quick draw even after being ordered to leave the pistol in its holster.

As if the embodiment of the whole screwed-up war, the Alaska Kid shot himself in the foot.

On my 20th birthday, I flew out of Da Nang back to Japan. Once there, I moved into my friend’s apartment in the Sagami-Otsuka neighborhood of Yamato. Having learned that something more incendiary than polite letters may be needed to get attention, I suggested reviving a form of the Duck Power newsletter.

A similar idea had already occurred to my roommate and two of his buddies. They claimed to have a line on a mimeograph machine recently used for an underground newspaper by some Air Force personnel at nearby Yokota Air Base.

We later found out that it was available because those airmen got busted for their journalistic efforts. They endured courts-martial, demotion in rank, and reassignment to distant duty stations.

Even without that knowledge, my friends and I knew protest carried a risk. We decided to move forward anyway. That weekend, a member of our budding cabal met with an airman he knew at Yokota.

Soon, the Navy reassigned the four of us to posts outside Japan. We never put our hands on the machine.

I spent the remainder of my active duty chasing Russian submarines from the Bering Sea to the Indian Ocean aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga. Fulfilling our mission, we worked twelve on, twelve off, seven days a week.

The old guard may not have known what to do about the debacle in Vietnam, but it could effectively reduce dissent to a faint quack in a vast, indifferent ocean.