I wrote this essay/memoir in mid-2019 as a reaction to the shaming and derision Joe Biden was receiving for caring enough about people to love them; to hug them. The photo of my father was taken by an unnamed friend of his in Sasebo, Japan, 1945.

My father chose to be a hugger, but behavioral norms change. Today, our culture is flirting with the idea that people who hug others, regardless of intent, should suffer societal censure. While there are justifications for this, I sense a net loss for humanity.

I have my reasons.

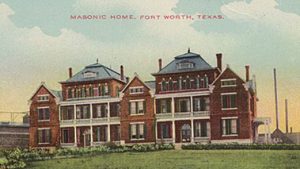

In 1934, my eleven-year-old father and his younger sisters were accepted into the Masonic Home in Fort Worth, an orphanage. The deepening of the Great Depression forced the relatives who had taken them in two years earlier to make some hard choices. To my father, this meant going from the expansive freedom of a boy on a south Texas ranch to the confinement of an institution.

Betrayed by life three times; losing his mother, then his father, and then his extended family; he shut down in anger and frustration. Huddled against the wall next to his bed in the dorm, he struck out at others and refused all appeals to engage in this new world.

The dorm mother sat on his bed and pulled him up to her breast, hugging him with fierce compassion. Although he struggled, she would not let him go. She held him tight in her cocoon of love until his emotional resistance crumbled. Crying out all his hurt and shame in her arms, he came to know that someone cared.

As a result, he soon emerged from his cloud of despair and decided to give this new situation a chance. His choice influenced his sisters, who chose to follow their big brother’s lead. It paid off. They all excelled in the communal environment, forging firm bonds with the staff, teachers, and fellow orphans that lasted their entire lives.

Eleven years after that life-changing hug, my father served as a platoon leader with the Marine Corps during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II. I could try to describe the horrible conditions and brutality of this campaign as it has been described to me, but I am convinced neither you nor I could understand it without living it. Suffice to say, this was a ruthless arena in which my father was a combat officer. He had been trained relentlessly to slay Japanese soldiers that had been trained just as relentlessly to destroy their enemies or to die trying.

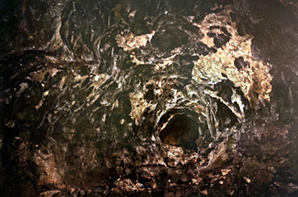

During one patrol, a drencher of a thunderstorm broke out, as it often did during this battle. My father and the Navajo Codetalker assigned to his platoon ducked into one of the many caves on the volcanic island.

As their eyes adjusted to the dark, their guts suddenly clenched in fear. A Japanese soldier as youthful as the Americans in front of him, but emaciated from hunger, stood with his back to the wall. He held a rifle with a bayonet attached, its point hovering two inches from my father’s heart.

My father said he felt oddly calm. He saw in this wretched warrior his younger self; scared, hungry, and angry at a cruel fate that had led him to such a dark place. Trained to kill, primed to kill, my father instead returned a favor. He gently moved the bayonet to the side and hugged his enemy, feeling him sob uncontrollably in his arms.

In that moment, both of these men chose compassion for the other. However, in so doing they defied the then-current behavioral expectations of their militarized cultures. Thus, due to their acts of basic decency, both of these men felt shame.

Yet they lived to pass on their emotional wisdom.

Twenty-five years later, my roommate and I strained and sweated with our Japanese neighbors as we spread several loads of gravel to resurface the driveway and parking lot of our small apartment house near the train station in Sagami-Otsuka. It was hard work that we did without speaking a common language, but we found a rhythm. Side by side we toiled as one until the job was done.

At the end of the day, we toasted each other with broad smiles as well as cold beer brought out by the wife of one of our neighbors. And one more thing, an important thing: we men and women, merely one generation past the mutually shared horror of World War II, bowed toward each other with humility and respect before going back to our apartments to clean up.

Having just returned to Japan from Vietnam during yet another bloody war, this small moment of peaceful, unified effort became a blessing that I still savor.

For the entire extent of his life that I was able to witness, my father comforted the lost and bereaved, sat in mute affirmation next to those in existential pain, and held the hands of those who needed to know they were not alone. But most of all, he hugged anyone who could benefit from his endless reserve of love.

Observing his effect on people led me to believe that the world needs these gentle mentors who adapted to the heartaches of life by giving more of themselves. Rather than strictly obeying and enforcing temporary social mores, we can learn from men and women like my father and, yes, Joe Biden, that there is a more profound way to serve humanity.